Top Tips for Buying a Used Datsun 240-260Z (1970-78)

Cliff Chambers•30 December, 2024

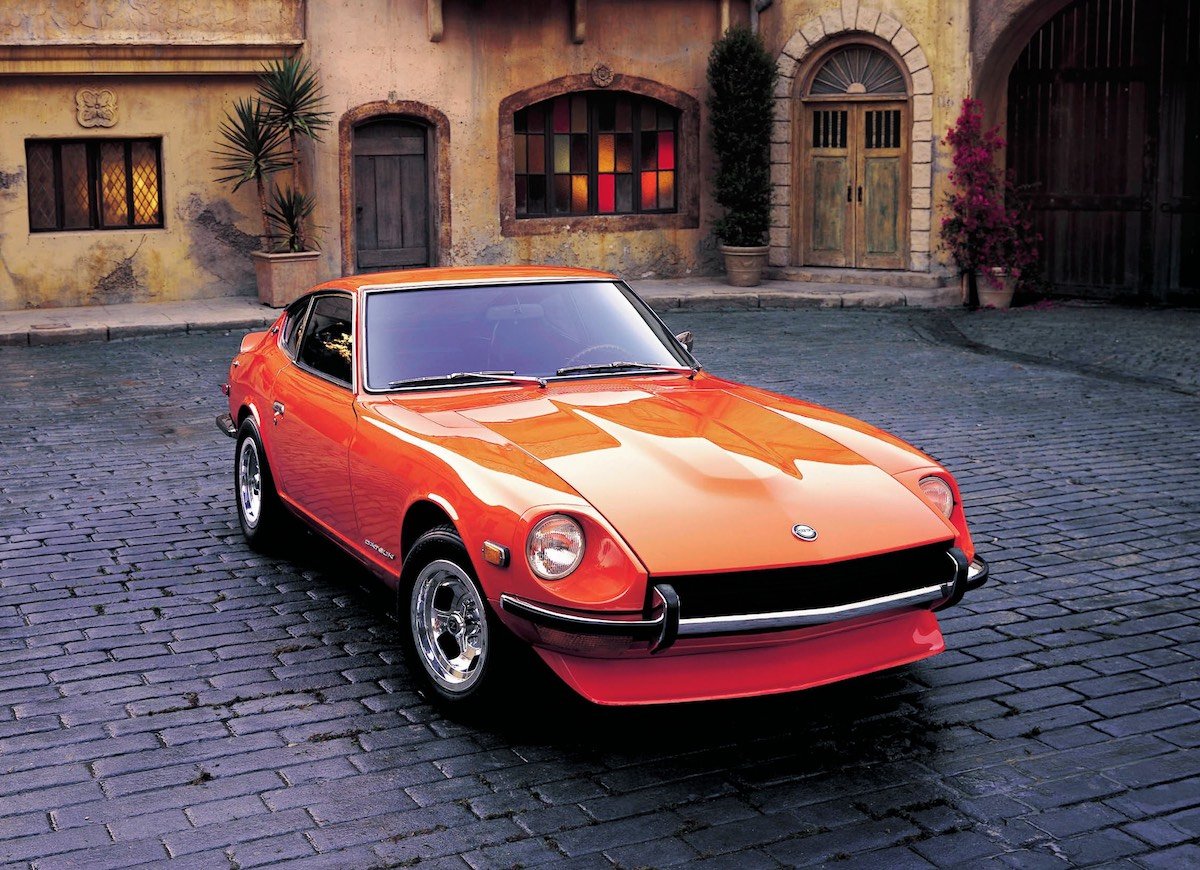

The Datsun 240Z debuted with a long-nose, raked windscreen and distinctive swooping profile that mirrored the Jaguar E-Type (Image: Nissan UK)

Once Jaguar’s E-Type had taken buyer expectations to impossible heights, only a manufacturer with more courage than experience would be bold enough to come up with the idea of a cut-price version. Enter Nissan with its Datsun-badged 240Z sports coupe.

In shades of what has more recently occurred with Chinese car makers copying European designs, Nissan's designers unashamedly copied the long-nose, raked windscreen and swooping profile of the Jaguar. The also borrowed the slinky Jag’s recessed headlights and its lift back access to the luggage area.

Beneath that elongated bonnet, Nissan slotted in its own 2.4-litre ‘L24’ SOHC inline six-cylinder engine, fed by twin SU-style Hitachi single-barrel side-draft carburettors, where the E-Type boasted genuine triple SU carbs. In Japan, where it was sold as the Fairlady Z, it was also offered with a pair of 2.0-litre straight-six engines, the ‘L20’ in ordinary variants and the peaky ‘S20’ from the original Skyline GT-R in the high-performance Z432.

First launched in Japan as the Nissan Fairlady Z, it was instead marketed elsewhere as the Datsun 240Z (Image: Nissan UK)

The free-spinning six puts its power to the rear wheels via a modern five-speed gearbox, which was vastly superior to Jaguar’s ropey old four-speed, with the sports coupe also emulating the E-Type’s fully independent suspension.

Late 1969 saw the Nissan Fairlady Z announced in Japan, but a year elapsed before Australia received its first Datsun-badged 240Zs. These early cars were all five-speed manuals but deliveries from 1971 included a smattering of three-speed automatics. Pricing was just shy of $5000, which made the sports coupe more expensive than local muscle car king the Ford Falcon GTHO Phase III, and $1600 more than the comparable Ford Capri V6.

A 2.6-litre, 260Z version was launched in mid-1974, at a time of surging inflation and fears of fuel shortages. Improvements included an extra 7.5kW of power, lower gearing for better acceleration, uprated tyres and reshaped seats.

The 260Z arrived in 1974 with a larger 2.6-litre engine as the name suggests (Image: Nissan)

Flow-through ventilation had been improved in 1973 but the Z cabin still got awfully hot during Aussie summers so the arrival of optional air-conditioning with the 260Z was a welcome addition.

Included in the range from 1974 was a 2+2 version of the Z on a longer wheelbase, with space in the back for younger children and some storage as well. These 2+2s were more expensive than the purer two-seat 260Z but still sold well and plenty have survived.

The North American market was kind to Nissan and by late-1977 more than 650,000 ‘Z cars’ had been sold there, most of them in left-hand drive.

The USA also had categories of racing that allowed the Datsun Z to show its superiority against other sports cars, whereas in Australia Nissan’s on-track focus remained on its tin-top sedans.

While early examples were two-seaters, 1974's 260Z also saw the introduction of a 2+2 model (Image: Nissan UK)

That didn’t stop West Australian Ross Dunkerton steering Datsun 240Z and 260Z rally cars to three consecutive Australian Rally Championships between 1975-77. Nissan’s robustly-engineered sports coupe was also successful in other motorsport events including twice winning the tough East African Safari Rally.

Despite the fuel-crisis and other 1970s economic forces aligned against it, Nissan held prices at realistic levels while offering a package that wiped out British MGBs and TR Triumphs, while also out-selling (and out-performing) Porsche's underpowered 924.

Values of early Z models remained relatively low until around the mid-2010s when cars remaining in the Japanese market began to sell for exaggerated sums. Early 240Zs in our market can now exceed $80,000, with 260Z 2+2s selling for up to $50,000.

It's only in recent years that the value of 240Zs has skyrocketed (Image: Nissan UK)

Nissan’s ‘Z car’ brought the essence of Jaguar’s E-Type to a much wider market. Its buyers were people who liked the E-Type’s low and sleek shape but aspired to a sports car that would start first time, every time, and go all day without needing roadside assistance.

Datsun 240 and 260Zs sold in decent quantities here, which is a good thing given that during the 1990s, before prices had risen substantially, many old and damaged cars were deemed ‘uneconomic to repair’ and either scrapped or stripped for parts.

Buying a Datsun 240Z or 260Z for the long-term means staying ahead of returning rust and not skimping on repairs. Those cautions aside, these are a car with inbuilt longevity, that are relatively easy to maintain and very enjoyable to drive.

With their timeless styling and strong market presence, the Z’s appeal is enduring.

The early Z's appeal is enduring, with these cars being easy to maintain and enjoyable to drive (Image: Veloce Publishing)

Things To Watch Out for When Buying a Used Datsun 240-260Z (1970-78)

Body rust, especially in the floors and windscreen pillars

Doors hard to close due to worn hinges

Engine valve train and timing chain noise

Clunks from worn rear half shafts

Excessive steering play due to steering box wear

Deterioration of dashtop and interior plastics

Valuation Timeline Datsun 240-260Z (1970-78)

🛠️ Timeline

Investment Rating

6.5 / 10

Cliff Chambers

Get The Latest

Sign up for the latest in retro rides, from stories of restoration to community happenings.

'1972â73 1-1024x675.jpg)