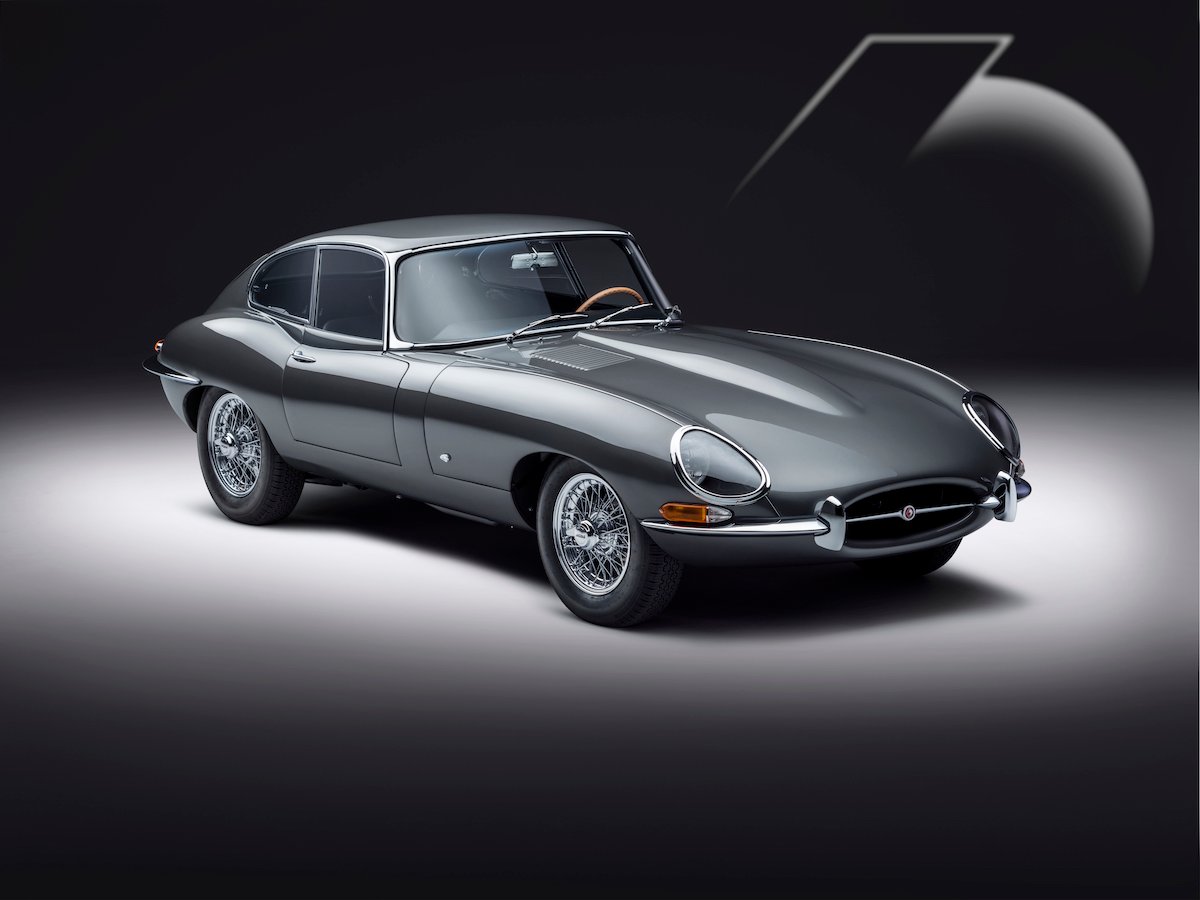

How the Jaguar E-Type’s gorgeous curves were shaped by an ace aerodynamicist using mathematical logarithms and lengths of wool taped to the bodywork to illustrate airflow.

The dawning of the 1960s promised a new age in high-speed travel. Britain’s first motorway, the M1, had opened and the space race was in full swing. Then, in March 1961, one month before cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin rocketed into orbit, Jaguar launched its E-Type sports car.

From late-1957, Jaguar had been secretly working on a new sports car to replace its aging XK120/140/150 model. Elements from the D-Type racer such as a sheet aluminium monocoque, aerodynamic bodywork, Dunlop disc brakes and Jaguar’s DOHC ‘XK6’ inline-six were incorporated – as was the knowledge that the D-Type’s live rear axle was well past its use-by date.

Prototype ‘EA1’ set the template for the E-Type’s sliver-of-soap shape, but its most significant feature was a brilliant, double-wishbone independent rear suspension, housed in a detachable pressed-steel cradle.

A second prototype, E2A, would surface in 1960, again clad in bodywork by ace aerodynamicist, Malcolm Sayer. He arrived at these gorgeous curves via mathematical logarithms, verifying his findings with lengths of wool taped to the bodywork to illustrate airflow.

All of which shaped the E-Type. The main monocoque was now welded from pressed steel (rather than aluminium) sections, to keep costs down. The potent 3.8-litre XK150S engine and gearbox sat in a front framework of square-section tubing, with a smaller frame ahead for the radiator. The double-wishbone rear end incorporated a limited-slip diff and inboard disc brakes.

The E-Type’s 3781cc, DOHC, inline six-cylinder engine featured triple two-inch SU carburettors and a 9:1 compression ratio, good for 198kW at 5500rpm and 349Nm at 4000rpm. This unburstable iron block, alloy head, seven main-bearing XK unit, which Jaguar had introduced in 1949, remained in production (in 4.2-litre guise) until 1992.

The E-Type was strictly a two-seater, available in roadster or ‘fixed-head coupe’. Aside from its flagrantly phallic shape, it boasted crowd-pulling features like a front-hinged bonnet and a dramatically rounded windscreen, necessitating three wipers.

Enzo Ferrari is supposed to have described the E-Type as “the most beautiful car ever made”. Certainly, this gorgeous, pedigreed sports car was as desirable as any contemporary Ferrari, Maserati or indeed, Aston Martin, all of which cost two to three times the Jaguar’s drive-away price of £2100 (roadster) and £2200 (coupe). Five hundred orders were taken on the Geneva show stand.

Of course, there were problems. The inboard rear discs were prone to overheat, the seats were bony and the non-synchro Moss four-speed ’box was bloody hard work. The now-prized “flat floor” versions of 1961-62 weren’t the best for occupant comfort.

But there was handling, in spades, and performance: Brit mag Autocar clocked 0-60mph in 7.1 seconds, 0-100mph in 15.9 and matched Jaguar’s 150mph claim (though no other testers ever did).

Many of the E-Type’s foibles were addressed with the Series 1 update in 1964, also introducing the torquier, 4.2-litre motor and all-synchro ’box. In 1966 an ungainly looking 2+2 coupe was added.

The Series 2 (1968) also made concessions to US crash and emissions laws, with a new dash and the scrapping of the headlight fairings, which looked great but diffused light horribly. The blinged Series 3 (1971), with a new, 5.3-litre SOHC V12, finally confirmed the E-Type as a plush grand tourer. A Series 3 manual roadster weighed 1515kg, an increase of more than 25 per cent over the original.

But the E-Type didn’t just win Jaguar a generation of drooling schoolboys; it was a sales success. When production ended in 1975 it had sold 72,250 examples, more than double its predecessor XK120/140/150. Just under 34,000 of those E-Types were roadsters.