This article was originally published in Beyond the Drive by Mazda Australia and has been reproduced on Retro Rides with permission.

In the early 1990s, Mazda was king of the hill when it came to production car endurance racing. From 1992-94 it won three consecutive Bathurst 12-Hour races with the FD RX-7, further cementing the rotary engine’s reputation for performance and reliability forged by the iconic Mazda 787B’s victory at the 1991 Le Mans 24 Hour.

Come 1995, however, and the ballgame had changed. There was a new venue, the race moving from Bathurst to Eastern Creek – now known as Sydney Motorsport Park – and the competition was much tougher.

Tired of being beaten by Mazda’s twin-turbo sports car, Porsche imported 10 examples of its latest 911 RS CS to homologate it for local competition, while Frank Gardner received permission from BMW to create a lighter, more powerful version of its E36 M3 called the M3R.

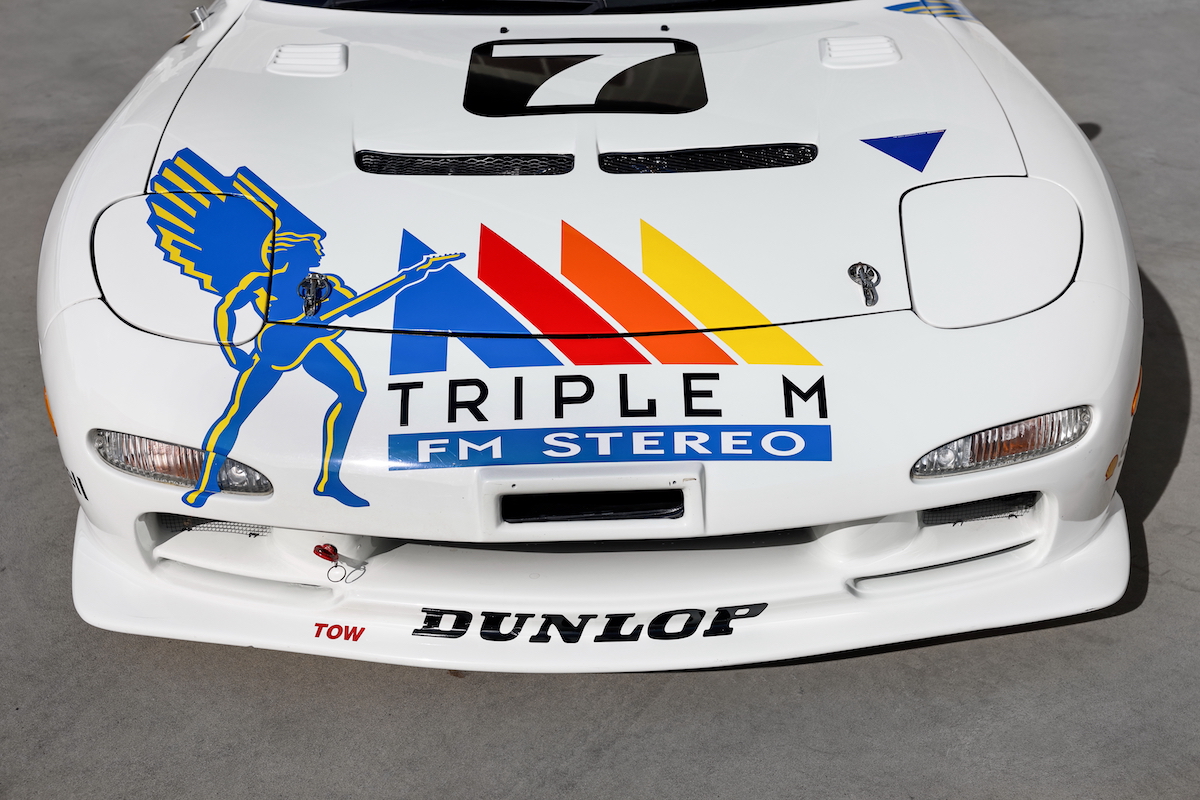

Far from being intimidated by this more potent opposition, Mazda returned serve with the RX-7 SP, a limited-run, Australian-developed homologation special that featured some 127 changes over the standard model.

Masterminded by the late Allan Horsley, Mazda Australia’s motorsports manager, more power, larger brakes, wheels and tyres, almost 100kg less weight, a shorter ratio diff with lightened flywheel, a 110-litre fuel tank and grip-enhancing spoilers were just a few of the modifications made to try and keep the competition at bay.

Someone who has intimate knowledge of the Mazda RX-7 SP is Australian racing legend John Bowe, who along with Dick Johnson shared the number seven car, while Mark Skaife and Garry Waldon shared the number nine car with Allan Grice acting as reserve driver. Bowe was part of Mazda’s 1992 assault on Mount Panorama but that was not his first association with the brand.

“It goes back quite a long way,” he explains. “My dad and his business partner were on the Mazda dealer council back in the 1970s [and] when Allan Moffat started racing the RX-7. They, as in the dealer council, tried to get Moffat to give me a drive. I got to know Horsley a bit and I think the RX-7 drive came about because of me knowing Horsley and us being dealers.”

Bowe shared with Gregg Hansford and while the sister car driven by Charlie O’Brien, Mark Gibbs and Garry Waldon won, Bowe’s abiding memory of the 1992 race isn’t quite as comfortable.

“We had trouble with the intercooler hose coming off. In fact, every time the car blew the intercooler hose off and I stopped to get it fixed, they filled it up with petrol. So, in the end I was busting for a leak and couldn’t get out of the car, that’s what I remember most about 1992!”

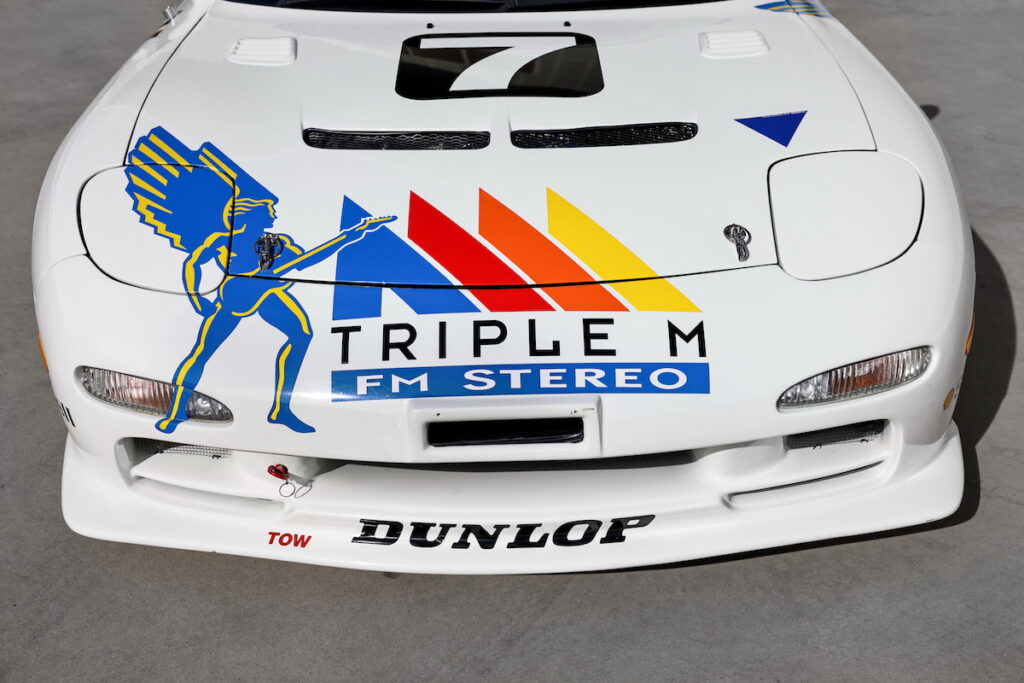

The arrival of BP as Mazda’s main sponsor kept the Shell-affiliated Bowe out of the RX-7’s driver’s seat for 1993 and 1994, but with Triple M coming aboard for 1995 there were no such issues. Dick Johnson – Horsley’s regular fishing partner – also joined the team, making for a formidable duo as the pair were the reigning Bathurst 1000 champions.

Despite the friendships involved, the project was very serious. “Horsley was a hard task master. He was tough, but he ran a very good show, the best of everything, did it properly. I remember in 1992 qualifying I think Charlie had been faster. I was doing a good lap and [Horsley] comes over the radio ‘come in, pit now’ because he didn’t want me to be chasing pole. Anyway, I ignored him and finished the lap, got pole, but he was ropable. I said, ‘I don’t know what happened, something with the radio’.”

Nothing about endurance racing – especially with production cars – is easy and while Mazda was flush with recent success, as any investor will tell you, “Past performance is no indication of future returns.”

A 12-hour test ended just past halfway with both cars expiring, leading to a contingent of Japanese engineers being sent to Australia to sort out some electronic issues. Even with the gremlins sorted, it quickly became clear that the race would be hard-fought.

Porsche’s new weapon was unbelievably fast and had dominated that year’s GT Production championship. Jim Richards and Peter Fitzgerald occupied the top two spots, with Richards winning five of the six rounds… and now they’d be sharing a car!

So it proved in qualifying, with Richards and Fitzgerald on pole followed by two other 911s and a second quicker than the quickest Mazda of Skaife and Waldon. Bowe and Johnson lined up sixth, but as the latter sagely put it, “Qualifying for a 12-hour race doesn’t mean an awful lot, it doesn’t matter whether you’re first or 10th or 20th on the grid.”

These words would prove prophetic, as by 20 minutes into the race Bowe was leading, but the fight was far from over. A seesaw battle would play out over the next half-day, the Porsches proving quicker but harder on their tyres, while the SP’s longer fuel range thanks to that 110-litre tank was a crucial advantage.

A safety car period gave the Mazda the upper hand, but the Richards/Fitzgerald Porsche was chasing hard, Bowe struggling with cramps in the closing stages due to dehydration. “Towards the end of the race I got cramp and started whinging a bit on the radio,” remembers Bowe. “Dick got on the radio about giving me a tune-up saying ‘Ah, you wimp, just drive the car.”

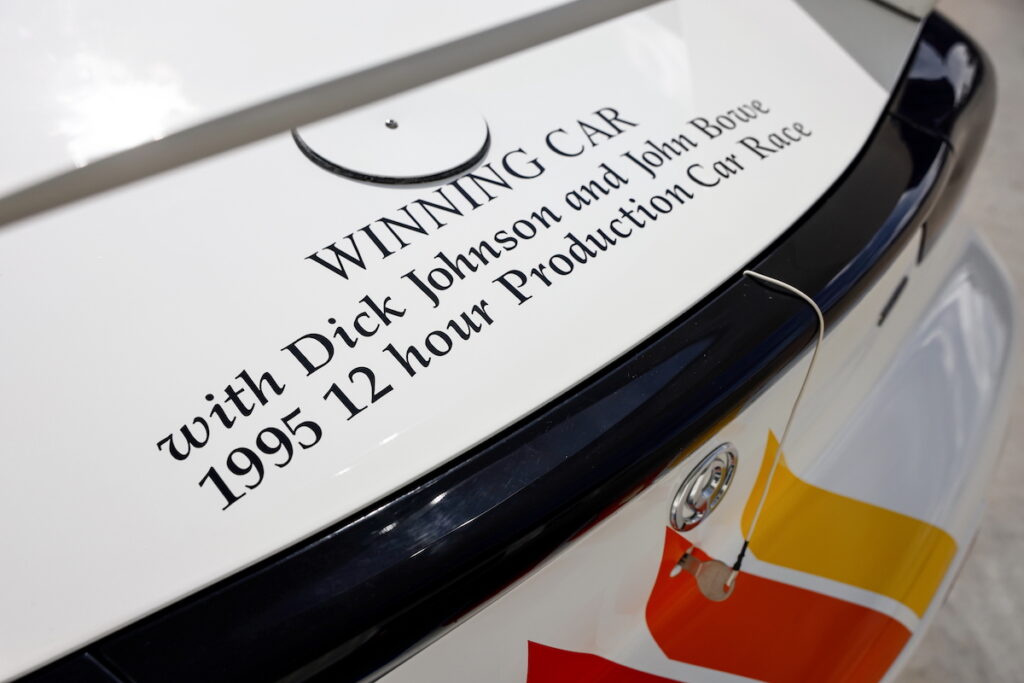

Johnson’s pep talk worked, with Bowe continuing to lead until the chequered flag with the Porsche finishing on the same lap even after 12 hours and 409 laps. The challenges only made Mazda’s fourth successive 12-hour triumph all the sweeter, in a car that bested its competition thanks to the hard work of talented Mazda Australia personnel.

“Mazda Australia Managing Director Malcolm Gough was very pro-motorsport, very supportive of it,” says Bowe. “The big thing about it to me was that [the RX-7 SP] was all done in Australia, it was a terrific thing.”

Today, the winning car lives a more relaxing life as part of Mazda Australia’s extensive heritage collection, still wearing its Triple M livery.