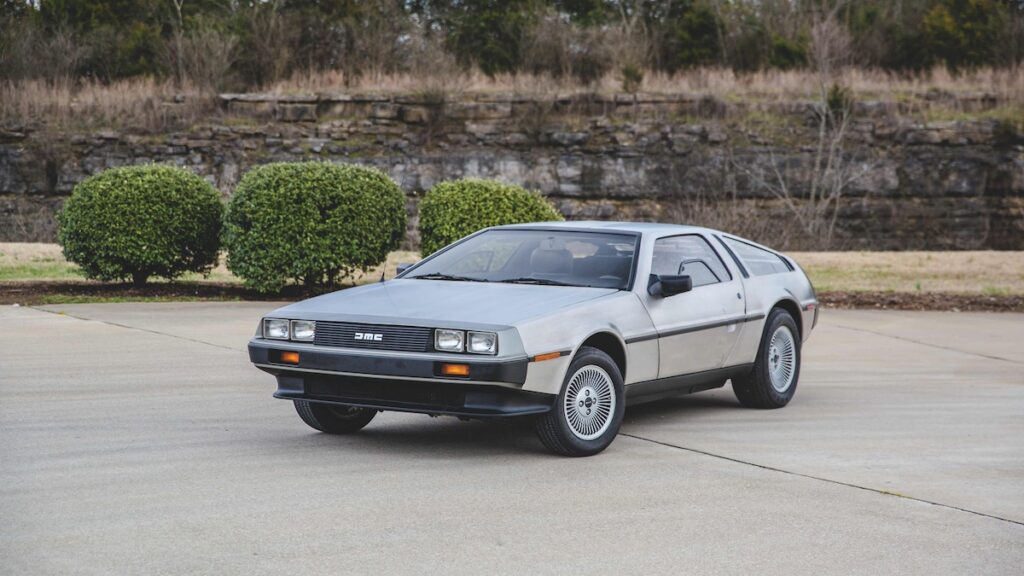

Best known for its starring turn in the Back to the Future movie franchise, the DeLorean DMC-12 is remembered more for its radical wedge-shaped design and gullwing doors, than the underpowered patchwork of poorly-assembled, proprietary parts that lay beneath its stainless-steel skin.

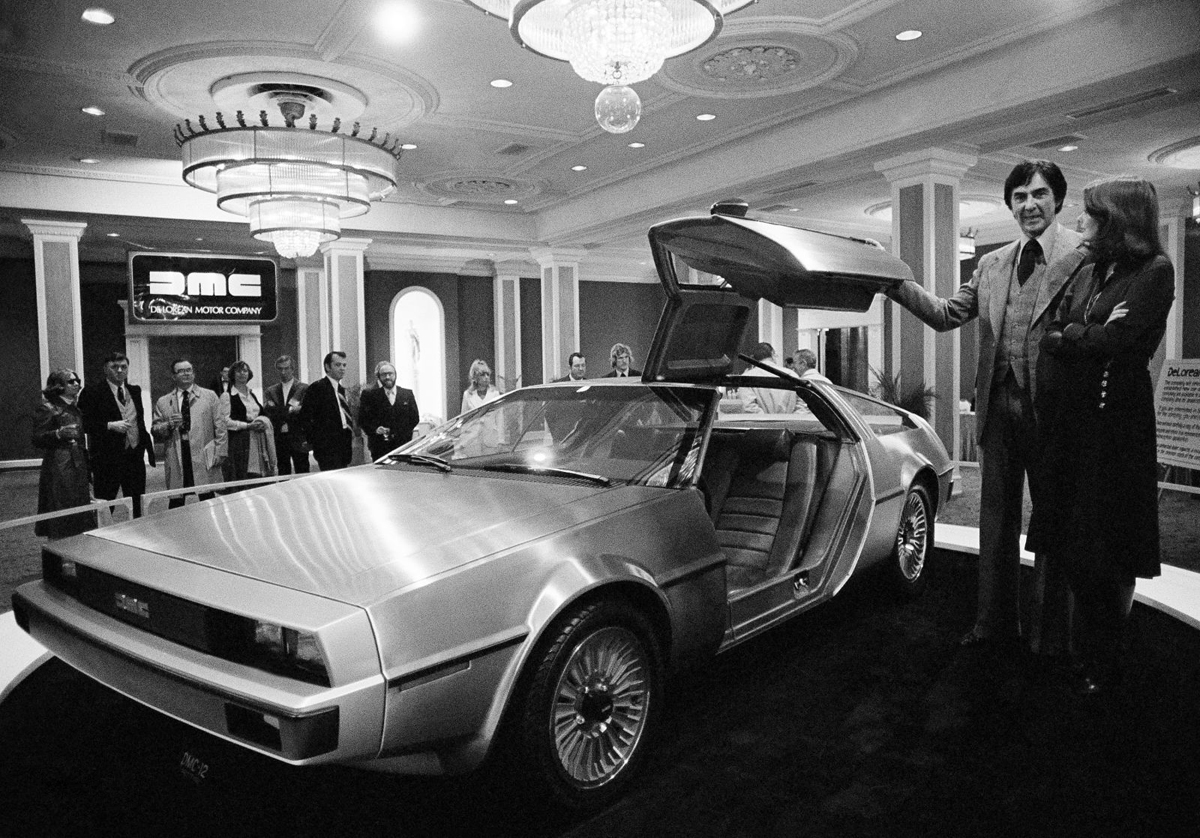

In 1976, the world thrilled at the announcement of a radical-looking, British-built prototype supercar. The personal brainchild of an automotive industry superstar, this wedge-shaped wonder had a rear-mounted engine, just like a Porsche 911, gullwing doors like the legendary Mercedes-Benz 300SL, and a Giugiaro-designed body skinned in stainless steel.

The DeLorean DMC-12 and its chiselled exterior proved to be a hollow promise. The engine was a wheezy French V6. It handled like an American barge crossed with a VW beetle. And the made-in-Britain label didn’t equate even to British Leyland build quality, but instead referred to Belfast, the epicentre of Republican rioting.

The Hollywood flim-flam around the DMC-12 – even nine years before its posthumous role in the Back to the Future franchise – reflected its creator. John Z DeLorean was an innovative engineer and marketer who by 1965, at age 40, was GM’s youngest-ever division chief, running Pontiac.

DeLorean made his fame with the maverick Pontiac GTO of 1964, the car that sparked the muscle-car movement. He then headed Chevrolet until, in 1973, he “dumped” General Motors.

In a climate of consumer activism, DeLorean touted an “ethical” car that would be cheap to run, boast unrivalled safety and have a rust-proof, energy-absorbing body of a radical new resin-sandwich material, skinned with stainless steel.

Celebrity pals like Sammy Davis Jr and Johnny Carson along with star-struck dealers seeded the DeLorean Motor Company, and in 1978, on the promise of 2600 jobs and 30,000 cars per year, the British government offered a £53m package to base the venture in “troubled” Northern Ireland.

DeLorean engaged Lotus’ Colin Chapman to help engineer the “dream car”. Lotus’ input, which amounted to a make-over of its own steel-backbone, fibreglass-bodied Esprit, was far less intriguing than the matter of Chapman’s personal consultancy fees. Upwards of US$17 million of government and investors’ money was paid into a Swiss account and later found to have been divided between Chapman and John DeLorean. Chapman would not live long enough to explain.

After three years, and a further £30m handout, production of the DMC-12 began in January, 1981. The ‘12’ in the moniker had stood for US$12,000, the planned price point to target Corvette. By launch time, it was a DMC-25.

DeLorean ran his eponymous business from a Manhattan penthouse. He earned a listing in the Guinness Book of World Records as Concorde’s most frequent flyer.

Meanwhile, the DMC-12 had evolved from an “ethical” car to one aimed at, in DeLorean’s words, “the horny young bachelor”. Novelties of its stainless-steel skin and gullwing doors aside, the car was an underpowered patchwork of poorly-assembled, proprietary parts.

DeLorean’s touted (and untried) ‘Elastic Reservoir Moulding’ resin material had proved inadequate for a chassis, hence Chapman’s ditching it for a familiar fibreglass body on a steel Y-backbone chassis, bearing front double-wishbones and rear trailing arms. Gullwing doors were an engineering nightmare solely in the service of style.

Kerb weight wasn’t bad at 1290kg, but 65 percent of that was in the tail.

Initial engine plans had centred on the Citroen-NSU Comotor rotary, then a 2.0-litre turbo Citroen four. In the end, mimicking the Alpine A310, the DMC-12 copped a 2.85-litre, fuel-injected V6, the so-called ‘Douvrin’ engine shared by Peugeot, Renault and Volvo in mainly large sedan models.

Euro versions of the engine boasted 127kW, but emissions-choked US versions offered a paltry 97kW. Transmission choices were a five-speed manual or three-speed auto. Even manuals took 10 seconds to accelerate from 0-100km/h.

The gimmicky gullwing doors proved ill-fitting, leaky and unreliable. Inside, DeLorean insisted on a space for a golf-bag behind the two seats. The interior was dominated by the tall spine of the chassis and the design and upholstery looked more mid-America than Maranello. DMC-12 cabins were notoriously noisy, and hot.

Sub-standard performance, handling and build quality rapidly doomed the DMC-12 in a US market already in downturn. John DeLorean claimed the honourable motive of trying to keep DMC afloat when, in October 1982, he was arrested for the alleged smuggling of US$24m of cocaine.

By then, DMC was already eight months into receivership, having built just 8600 cars. These included two of a commissioned 100 ‘Gold’ DMC-12s for credit card giant American Express, featuring 24K gold plating on the stainless steel.

On the upside, the DMC-12 became one of the most famous of all film cars, thanks to the Back to the Future series which commenced in 1985. In another appropriately unusual footnote, 12 massive pieces of steel tooling from the DMC factory were later taken by ship to Kilkieran Bay, on the opposite side of Ireland, and sunk into the sea as anchors for salmon-farming cages.