For the past 116 years, Bugatti has been committed to pushing the boundaries of possibility in automotive engineering, proudly infusing its cars with an inimitable blend of speed and elegance.

The French brand’s latest effort, the Tourbillon, clearly embodies that ethos, with it particularly drawing upon the past 20 years of experience developing top-speed monsters including the Veyron and Chiron.

However, the Cosworth V16-powered Tourbillon hasn’t just been based off knowledge of the recent past, with a clear design link between it and one of the brand’s most truly iconic cars, the Type 57 SC Atlantic of the 1930s.

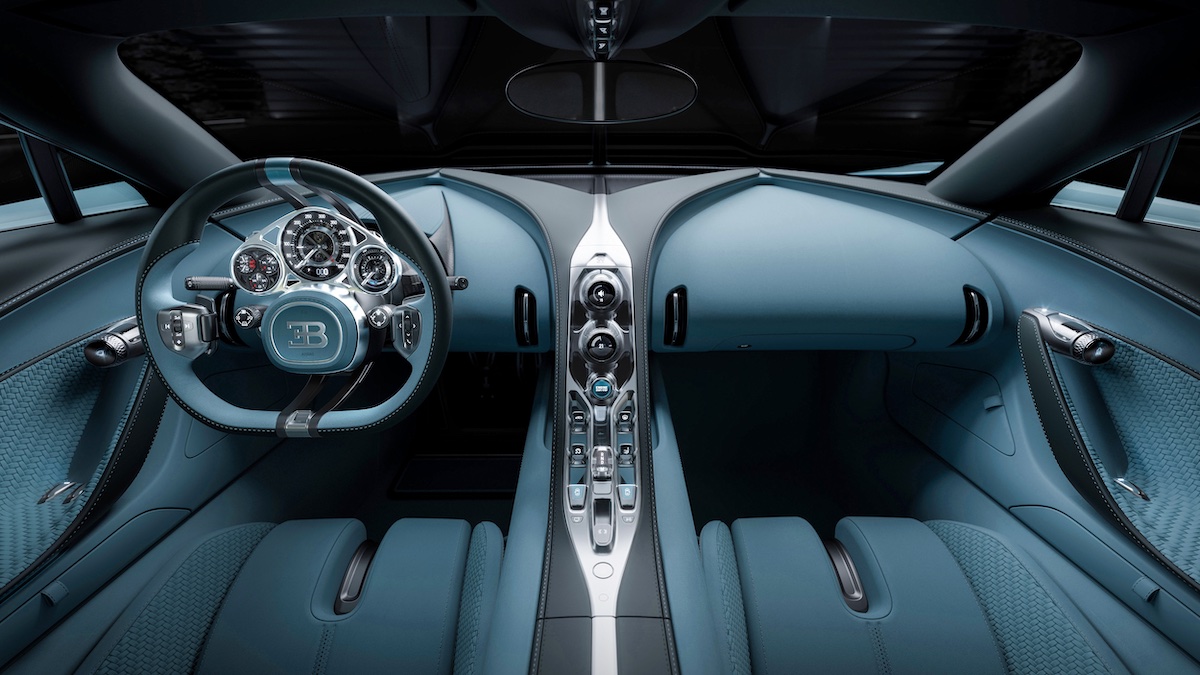

This is fitting because Bugatti has long made a point of building cars that transcend contemporary trends and instead look to resonate through the ages and evoke a sense of true timelessness; conjuring emotions and stirring the soul, irrespective of the year and era.

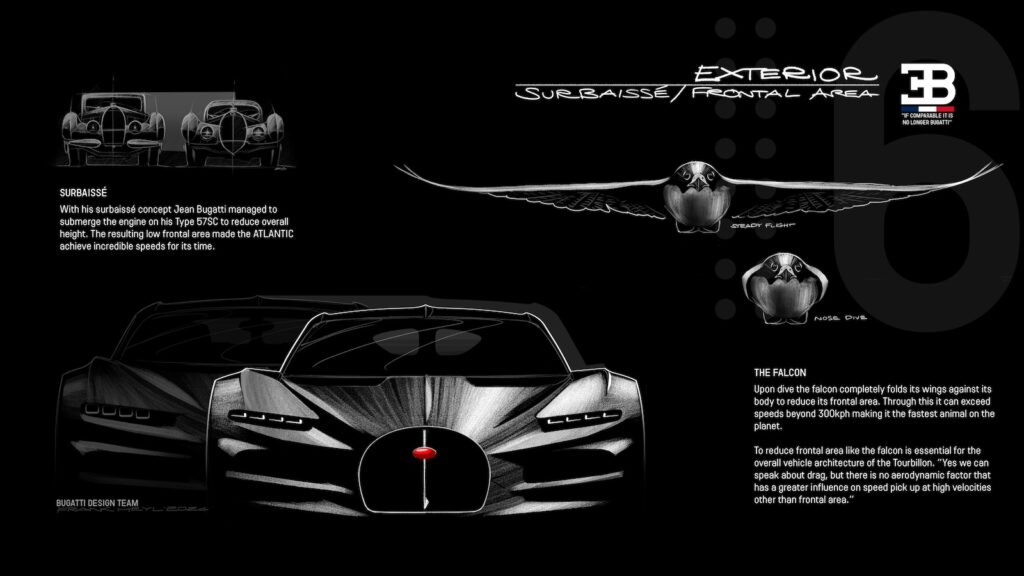

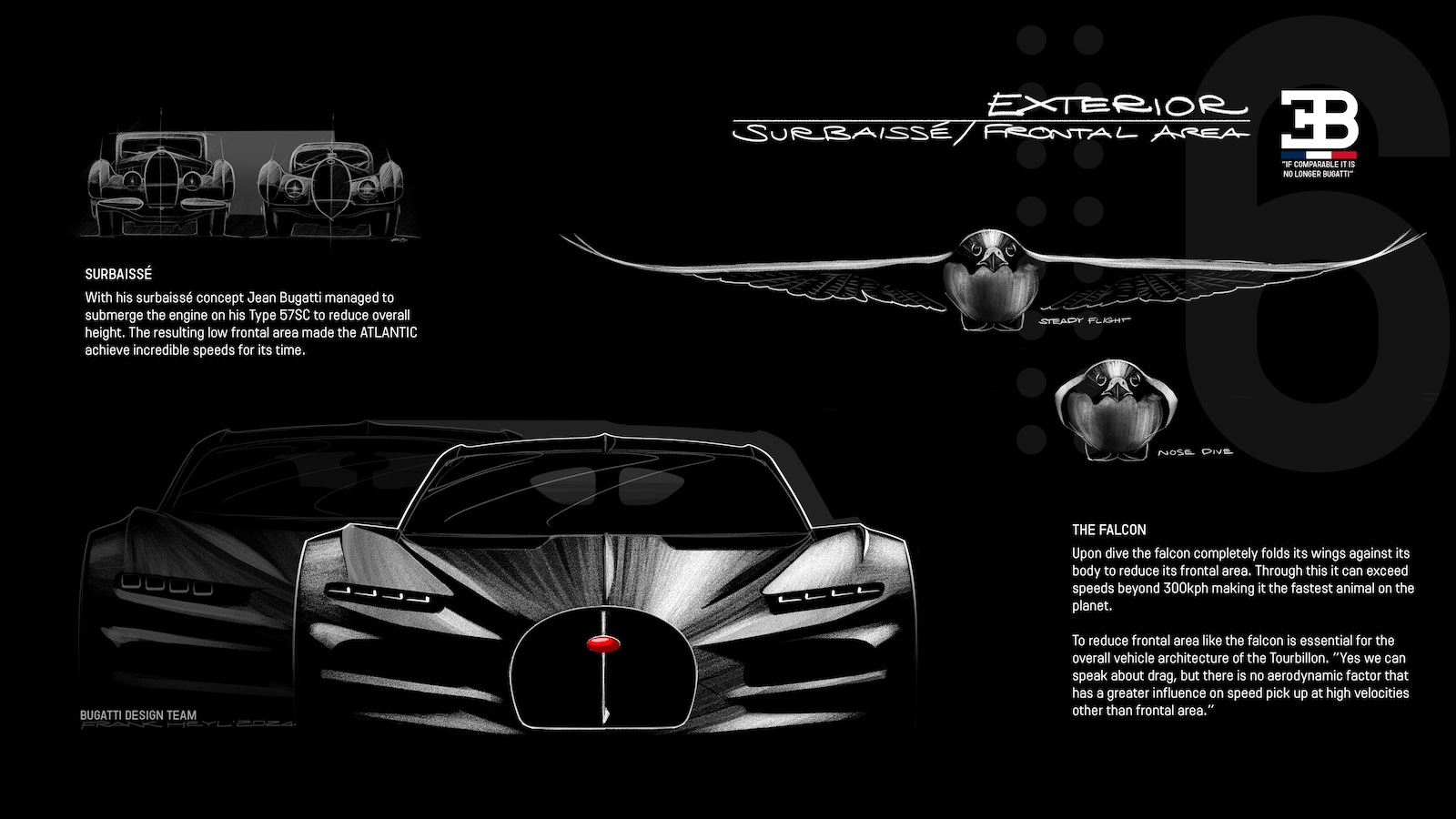

One way the brand accomplishes this is through its ‘surbaissé’ design concept, which Jean Bugatti developed in the early 1930s for the Type 57.

“By submerging the engine below and behind the front axle, the hood, driver, and roof could be lowered, maximising aerodynamic efficiency,” notes Bugatti design director Frank Heyl.

“It was unlike any other car of the time. And that same philosophy has been applied to the Tourbillon. With the Tourbillon, its purpose is to combine elegance with speed.”

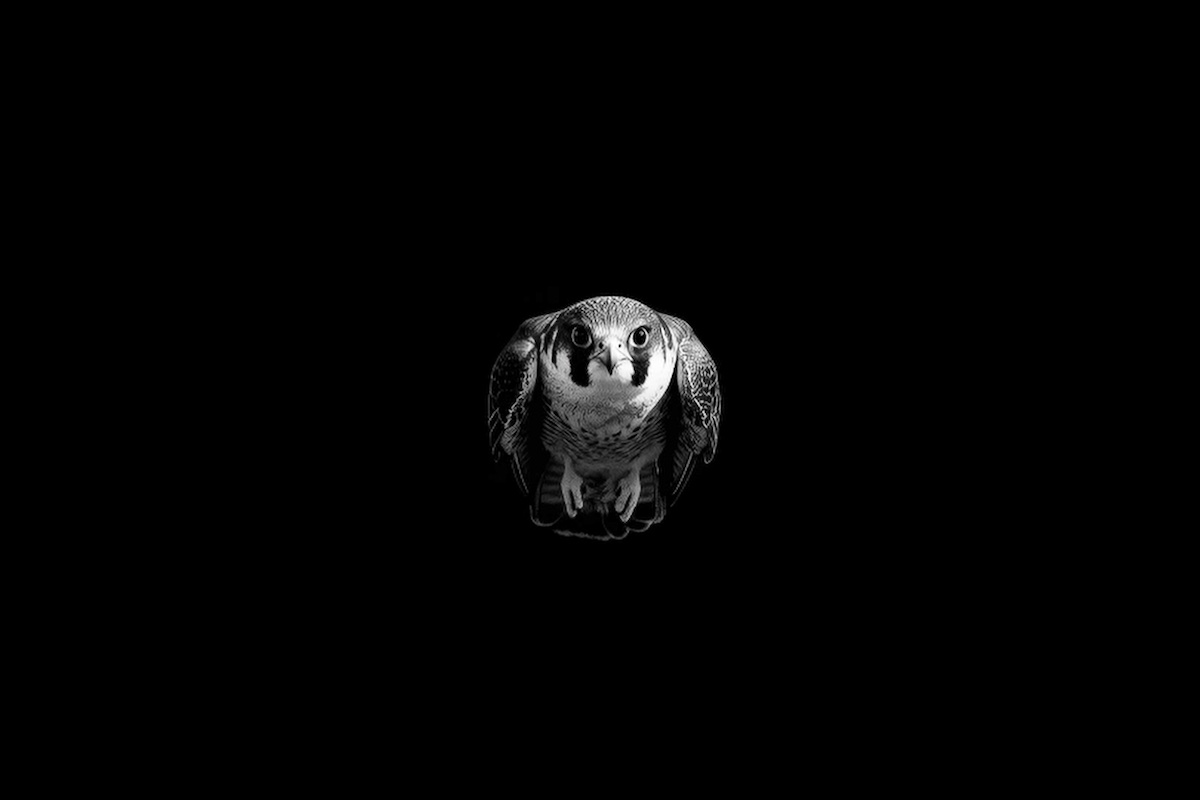

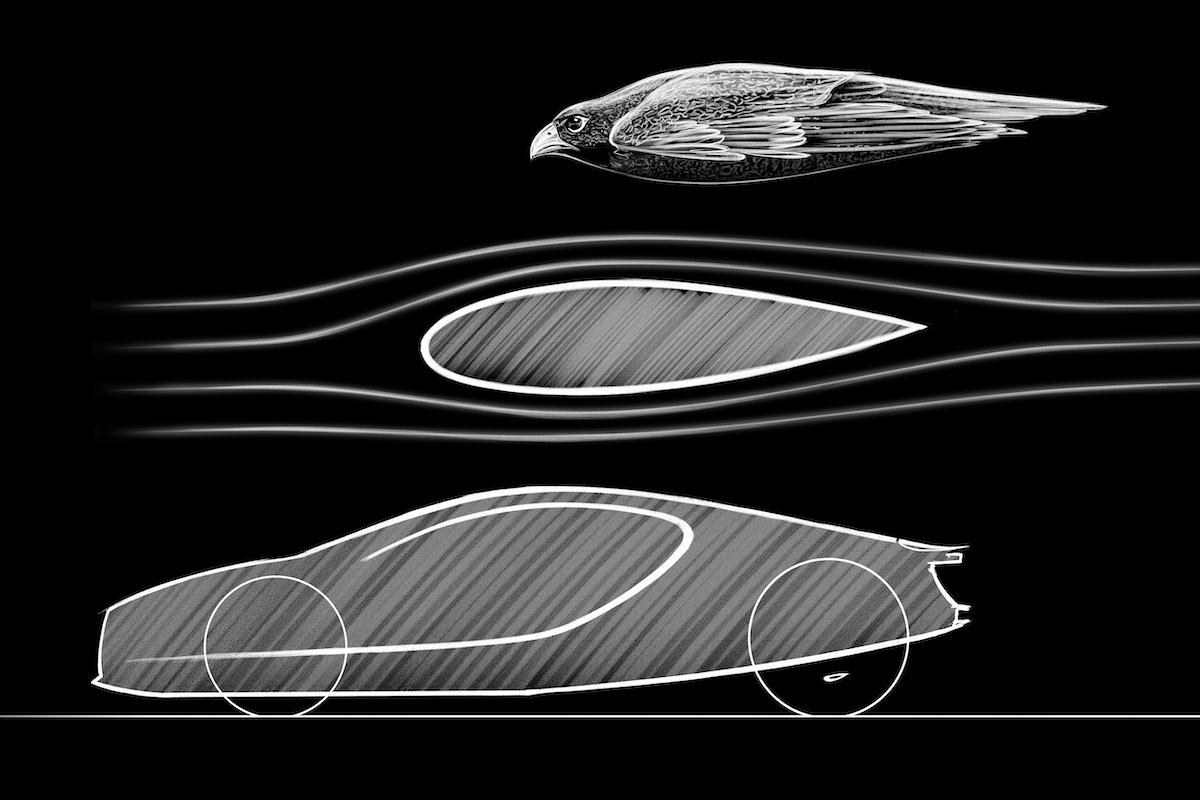

As with many of the finest pieces of design work of the past century, the inspiration for this iconic design draws not upon sheer mathematics, but rather the animal kingdom.

“A peregrine falcon is a marvel of biology – a bird that has mastered the art of aerodynamic efficiency in the pursuit of speed, tucking its wings in when nose-diving towards its prey,” Heyl explains.

“And why does it do that? It’s to reduce its frontal area.”

This same nature-based principle that underpinned the Type 57 SC Atlantic has thoroughly guided the design of the Tourbillon right from the car’s conception. Knowledge from the Veyron and Chiron high-speed programs also proved invaluable, too, as aerodynamic balance is a critical requirement for unlocking speed.

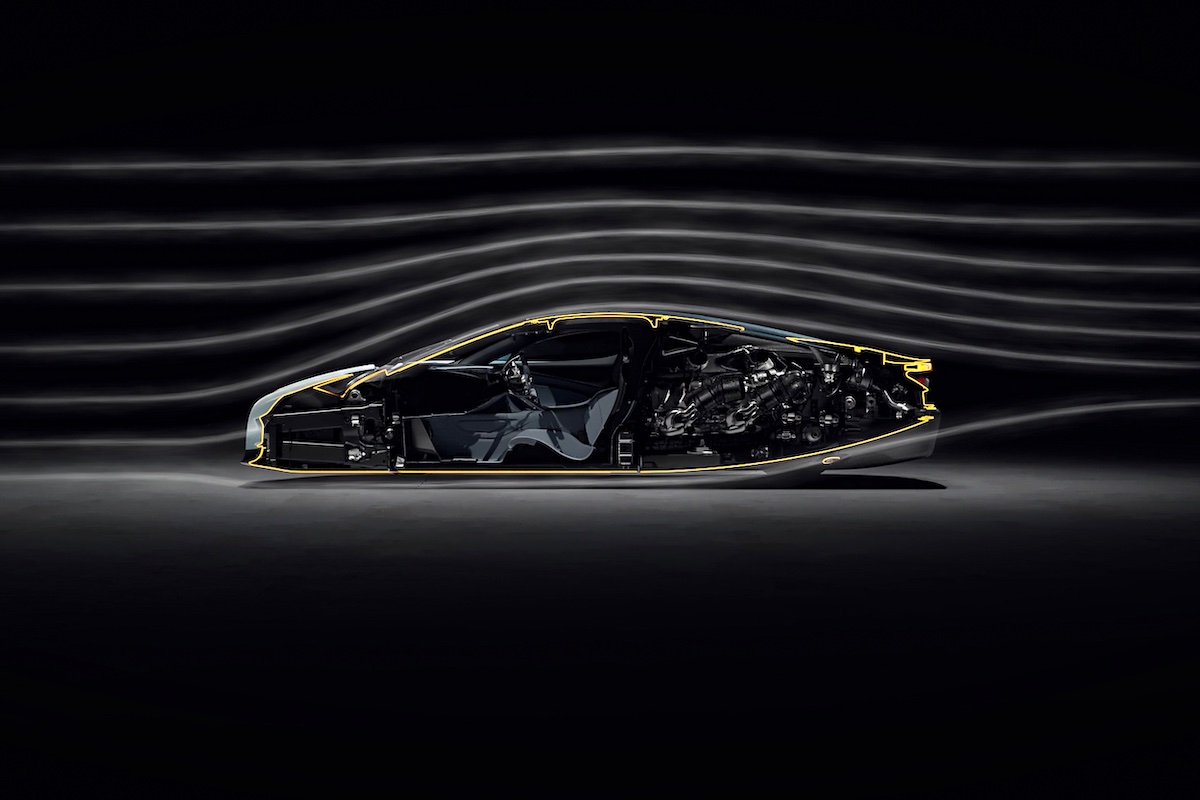

A n extraordinary amount of downforce is required to balance out the amount of lift generated by a car travelling at 445km/h, and in order to achieve this without generating excessive drag, the base shape of the car needs to be perfected from the very outset before any further aerodynamic aids are even considered.

Much like the peregrine falcon, the Tourbillon’s core form is that of an elegantly smooth and streamlined teardrop, from which the Bugatti design team could work their magic.

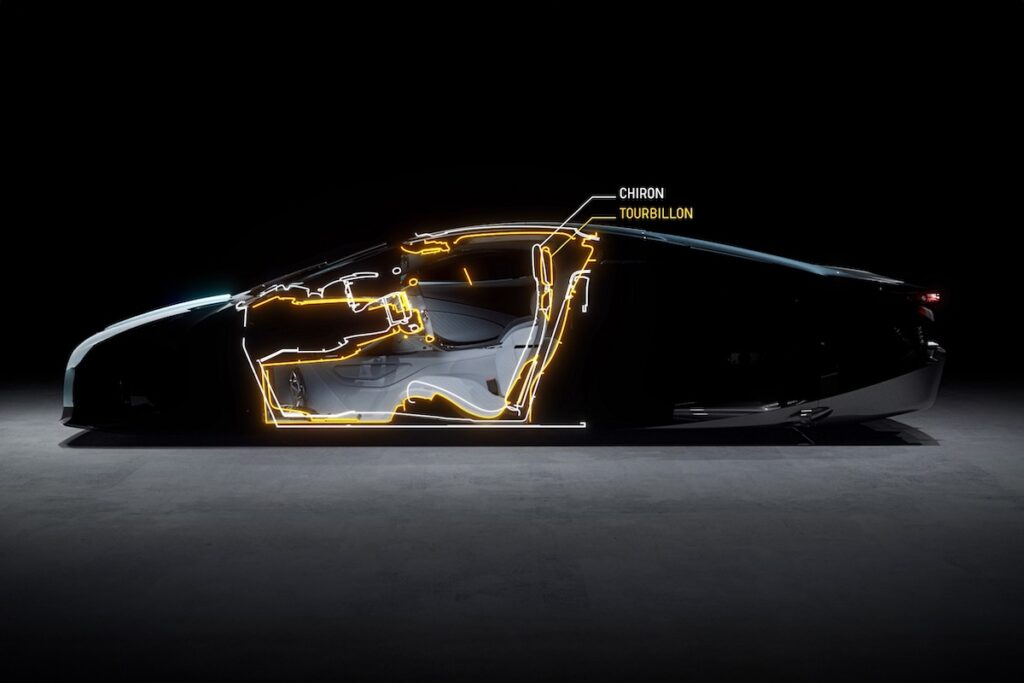

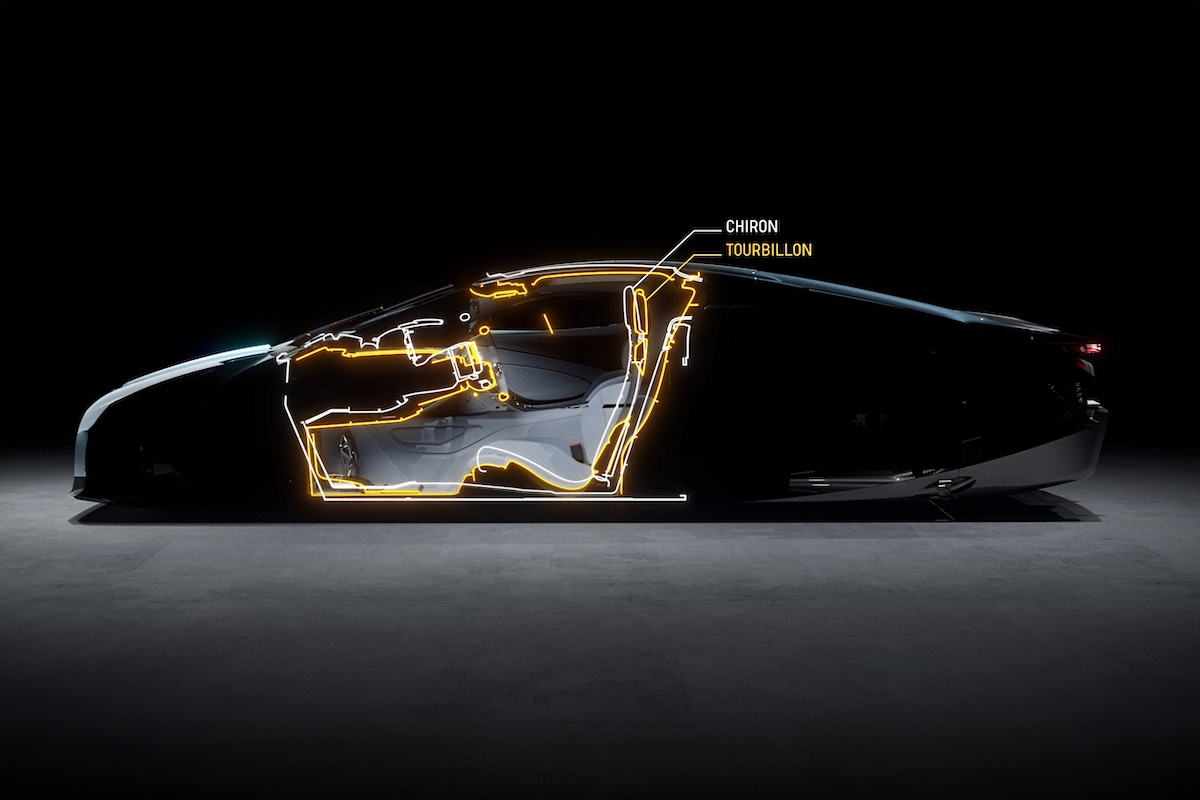

Compared to the Chiron, the Tourbillon features a much-reduced frontal area, lower height, and narrower cabin, all while maintaining the same space and ergonomic proportions in the cockpit.

The entire volume of the cabin shell, which has been lowered 33mm deeper into the carbon fibre monocoque, bestows it with extreme proportions, with the cockpit crouching low in between the two front wings.

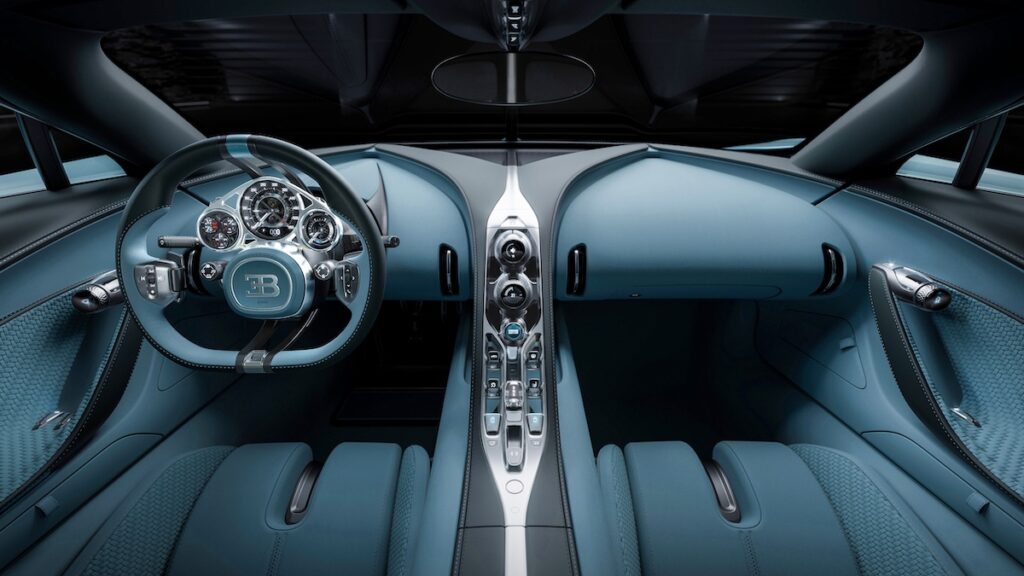

Reducing the vehicle’s overall height yet further, the two seats are mounted directly to the monocoque, with the steering wheel and pedals instead able to adjusted longitudinally to suit each driver.

The iconic Bugatti ‘horseshoe’ grille has also been widened, feeding air into the two radiators to its left and right, entering a high-pressure inlet before expulsion from a low-pressure exit at the top of the bonnet. This intelligently curated pathway creates a pressure drop, thus maximising the efficiency of the air flowing through the radiators.

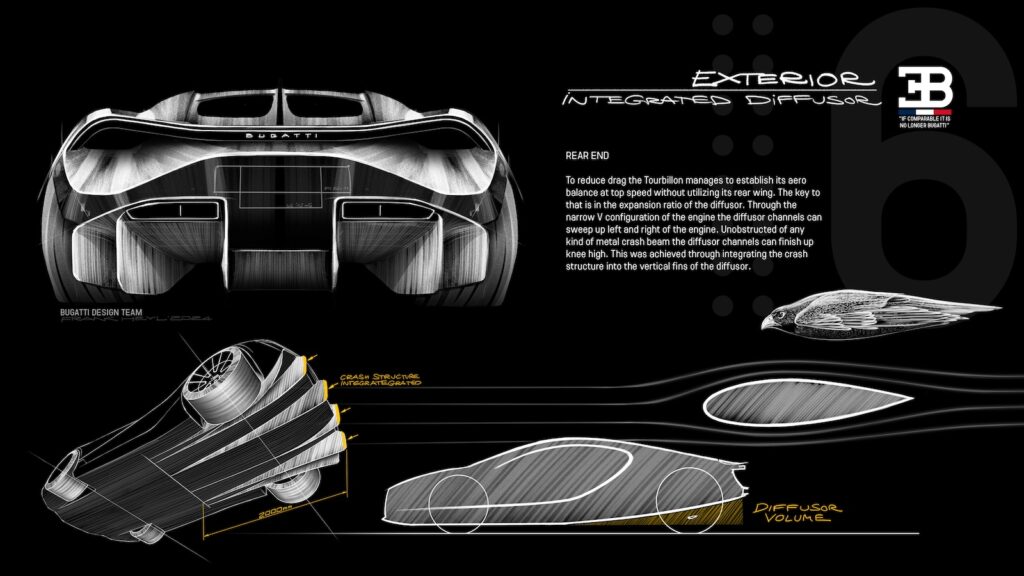

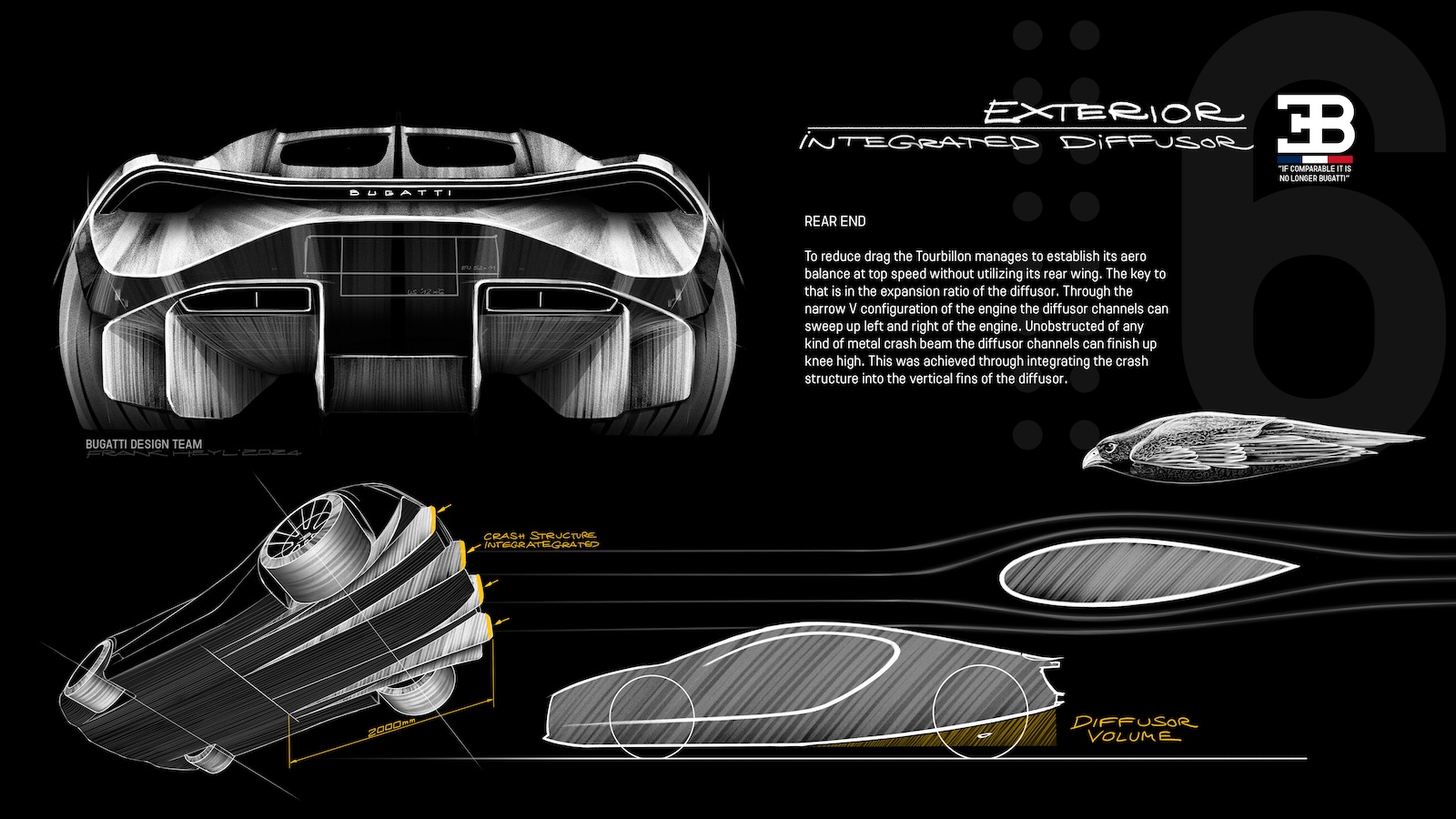

Great pride was also taken by the Bugatti design team in enabling the Tourbillon to travel at very high speed without the need to raise the rear wing thanks to its functionally optimised diffuser. Sitting entirely flush against the bodywork, in a marvel of sleek design and evading the disadvantages of drag, it makes the concept of aerodynamic balance – tempering lift with wing-less downforce – a reality.

Composed of multiple diffuser channels almost two meters long, beginning underneath the passenger seats, the diffuser runs to a very tall exit at the rear of the car where, at its trailing edge, it meets the exhaust outlets for that mighty V16 engine.

In another moment of engineering and design excellence, the exhaust gases energise the already accelerated airflow emerging from the diffuser, enabling it to further reduce air pressure and maximise the downforce produced.

Revelling in the juxtaposition of its beautifully slim light arrangement and the fragmented, technically driven surfaces of the diffuser, the rear of the car is given an aerodynamically efficient proportion while still emphasising the perception of width and presence.

“None of what we have achieved with the Tourbillon, are easy things to do. They’re only possible if you implement this kind of strategy from the very first pencil stroke,” adds Heyl.

This design strategy championed by Jean Bugatti in the 1930s was clearly a stroke of technical genius that has withstood the test of time, and now clearly carries into Bugatti’s future with the Tourbillon.